Reflecting on the Opportunity Myth

I have thought about The Opportunity Myth every day since it was released, and I will continue to think about it every day for years to come. It is such a significant report, I want to elevate the value of reading this one closely – for understanding – and share how I am trying to make sense of it and what it is leading me to do differently.

TNTP is the pacesetter of our field in storytelling, and they did it again – in fact, I would say this is their best work yet. It is an emotional view into the heart of daily instruction in American schools. I am sure randomized control purists will have methodology points of feedback, but as someone who observes about 200 lessons a year leading an organization that has seen about 3,000 classrooms, the report rings so true to the patterns I have seen play out across schools, grades, and state lines that I think the findings should be believed at face value. And that is what makes it emotional.

SO WHAT DID THE OPPORTUNITY MYTH REVEAL?

-

Students have big dreams: 94% of students surveyed aspire to attend college, and 70% of high schoolers have career goals that require at least a college degree. I don’t think grown-ups should dictate career aspirations of students (i.e. all kids should go to college), but I do think a meritocracy is based on the idea that students who have these aspirations should get the tools to pursue them. Well, it turns out, they want college.

-

Students are working hard: Students were working on activities related to class 88% of the time. They met the demands of their assignments 71% of the time, and more than half brought home As and Bs. For the most part, students are pulling their weight.

-

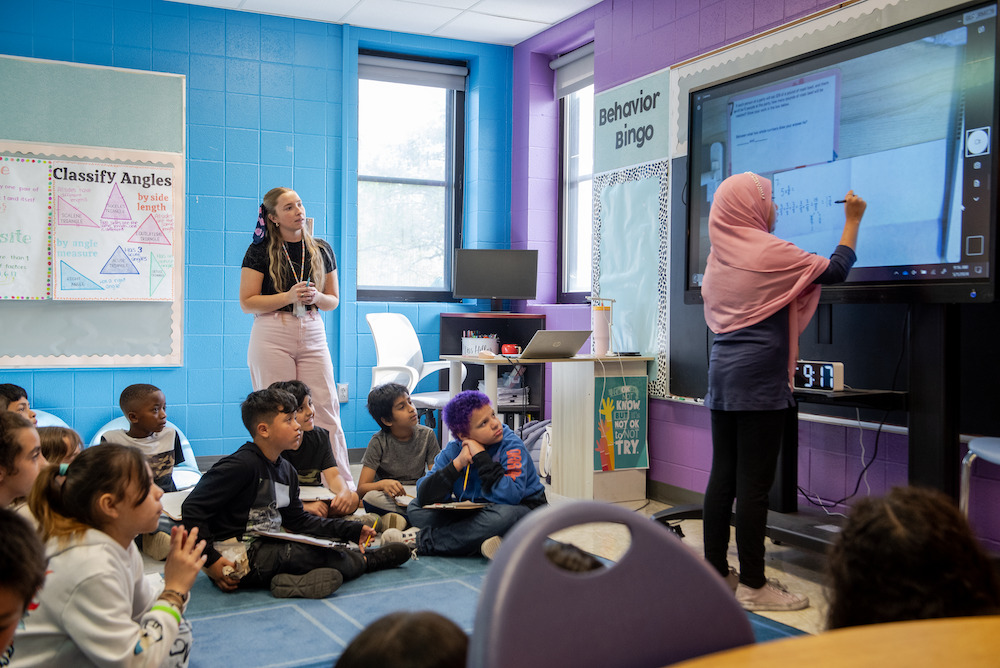

Students are underestimated – especially students of color – and they know it: Nearly 40% of classrooms that served predominantly students of color never received a single grade-level assignment. Compared to classrooms comprised of mostly students of color (>50%), classrooms with mostly white students tended to receive 3.6 times more grade-appropriate lessons.

Reading The Opportunity Myth felt like seeing the roots of the achievement gap. You can’t help but mourn all the potential we are missing out on as a country.

The only piece of my lived experience that I wanted to call out beyond the report is the fact base about just how hard teachers are working and how much they want to learn and grow and help their students.

-

Teachers work, on average, 53 hours per week

-

82% of teachers support the content of their state’s academic standards

-

79% of teachers want training on the standards to teach their students more effectively

-

93% of teachers say they welcome feedback from their school leaders; yet 30% feel like they get timely and useful feedback*

The ace in our pocket in this noble profession is our collective heart for students: no one enters teaching with malintent. The fact that daily instruction does not prepare students for their aspirations in sweeping numbers is happening alongside extraordinarily hard work and eager learning from the vast majority of educators. Both can be true.

The consistency of the findings points to systemic issues that will require some understanding of history and a hard look at our ingrained practices to change. In particular, it presses on the idea that, “good teachers meet students where they are.” If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, I suspect the source of why good people are habitually under-challenging their students has to do with taught and reinforced expectations that run through pre-service, orientation, principal feedback, and water-cooler culture. This will not be easy to change, but The Opportunity Myth invites us to flip this mantra to “good teachers give all students access to challenging work with the support they need to access it.”

I spent almost a month teaching my 7th graders subtraction with regrouping, and it was the wrong decision. I did a pre-test, and a lot of my students were not able to do this basic skill, so I went back to 3rd grade. During that month, the students who already knew how to subtract were bored out of their minds, and the students who didn’t know (but had already sat through plenty of lessons on the subject) got little that was new. And they all felt talked down, too. They called it “baby stuff.” I lost a lot of time that could have been spent on understanding concepts like integers for the first time (concepts that could have easily reinforced the meaning of subtraction and place value that were the root of their regrouping misunderstandings). That month put my students further behind. And I will admit that I complained to my colleague teachers about how far behind students were (which was true) in a way that made it seem like there was nothing to be done about it (which was not true).

Our paradigms about what we are supposed to do and our biases about who can do what work follow us straight into our daily instructional choices. We bring all the flaws of humanity to this human work of teaching, which is why we need a loving but challenging community to think through the choices we make and see them in a larger context. So rarely do we have time or space for this in the daily grind of school. However, The Opportunity Myth shows us the costs of our current paradigm. And invites us to reconsider.

SO WHAT AM I GOING TO DO?

-

I want to become a student of history and understand the roots of the prevailing identity badges we educators wear that contribute to these widespread practices. I want to listen to people who have been doing this work longer than I have to understand their perspective.

-

In our work with partners, I commit to looking more closely at the evidence of equity in access to high expectations – particularly for students in poverty, students of color, students with disabilities, and English Language Learners. Who is in this class? Who is not? Where are they? What are the expectations for their work? Why are they different? I also commit to look for evidence of equity in my daily interactions and decisions personally – knowing I can be a good person but also flawed and full of bias.

-

I have been complicit in avoiding hard conversations about grading practices because they scare me. I know the emotions students and parents carry around grades, and I see how much easier it is to make it easier to do well. But if this adds up to sending the wrong signals to students and families about their true level of preparation, we simply have to wade into these waters. I commit to understanding grading approaches and options better, even if it is hard.

I have never been in a school that does not have truly inspiring posters and artwork promising their students that if they work hard, they can achieve anything. Students should hear those messages every day, but they also need to see it in the work they are asked to do every day. And they know it when they see it.