Centering Affirming Relationships in Core Instruction

People need to feel trusted, supported, and affirmed in order to thrive. Learning environments grounded in trust have led to measurable student gains in attendance, behavior, language growth, and academics. We know that school leaders, teachers, and staff need to experience affirming conditions in order to deliver equitable instruction and that students—particularly students of color and multilingual learners—need to experience affirming conditions to engage in learning experiences fully.

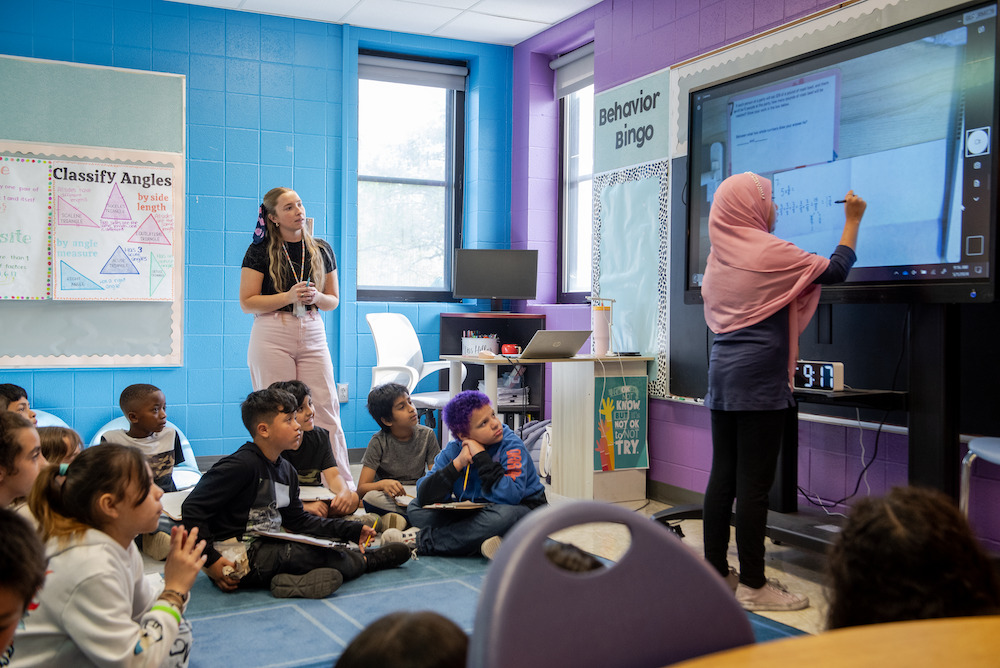

However, despite their documented influence on academic outcomes, support for relationship cultivation and social-emotional learning are primarily developed, planned, and implemented separately from traditionally “academic” supports for students. We can easily understand the importance of relationships in an advisory program—but what does it look like to cultivate affirming relationships during a fourth-grade math lesson? There is not a clear pathway for how leaders can meaningfully integrate social-emotional learning in their academic strategy and support affirming relationships at every level of the school community.

That’s why Instruction Partners has embarked on a multi-year research project to understand how to center affirming relationships in students’ learning experiences in core instruction. Through this project, we aim to codify key strategies and practices that can be replicated in schools throughout our country.

At Instruction Partners, we define an affirming relationship as “one in which people acknowledge and value the genius that already exists within every community member.” The term “genius” is rooted in the work of Dr. Gholdy Muhammad, author of Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. Sources of genius can be found in home language, personal and professional experiences, individual identity, community, history, and culture. An affirming relationship develops when people see other people’s sources of genius as equally valuable to their own.

This year, we conducted a landscape analysis, synthesizing research and interviewing 14 high-performing organizations as well as several individual experts. As we assessed the common themes, commitments, and strategies, we found that the Search Institute’s Framework for Developmental Relationships represents some of the most comprehensive, well-researched, specific, and widely used work in this field.

The framework is organized around five key elements of affirming relationships:

- Express care: Show me that I matter to you.

- Challenge growth: Push me to keep getting better.

- Provide support: Help me complete tasks and achieve goals.

- Share power: Treat me with respect and give me a say.

- Expand possibilities: Connect me with people and places that broaden my world.

We’re excited to build on the Search Institute’s framework in our research. As we consider how the five key elements show up in classrooms, the results of our landscape analysis indicate that sharing power will prove to be one of the most difficult to implement and one of the most critical to success.

The Search Institute names four requirements for shared power:

- Respect me—Take me seriously and treat me fairly.

- Include me—Involve me in decisions that affect me.

- Collaborate—Work with me to solve problems and reach goals.

- Let me lead—Create opportunities for me to take action and lead.

Sharing power requires recognizing that each and every student has inherent genius to contribute to their class’ learning—including the learning experience of their teacher—and creating opportunities for them to do so. That is, this element necessitates that teachers occasionally and purposefully step out of the role of “expert” and encourage their students to step into it. It creates new possibilities for how we approach teaching and learning as we think about where and how we can give students real agency and how traditional school structures might act as barriers to meaningful change.

We expect sharing power to be particularly challenging to implement because it requires fundamental mindset shifts about the teacher-student relationship—and the entire traditional hierarchy of schools—but those fundamental shifts are precisely the reason we believe this element is absolutely crucial: only when adults are willing to work with students as capable shapers of and contributors to their own learning, rather than as passive recipients of information, can affirming relationships develop in the classroom.

Over the next two years, we’re piloting affirming relationships work with a selection of our partner schools. We seek to answer fundamental questions about fostering equitable instruction and improved student experience:

- What are the instructional systems and actions that are necessary to strengthen affirming relationships between adults and students, such that their learning experiences are stronger? Are they content-specific?

- How do we make changes to existing affirming instructional actions and preconditions?

- How do we use and help our partners center student voice, particularly of students of color experiencing poverty and multilingual students, in decisions, actions, and the design of improvements?

We’re so excited to help bring the five key elements for affirming relationships to life in our partners’ classrooms and support all students’ learning success. If you are interested in bringing this shoulder-to-shoulder work to your school, please get in touch.

We’ll continue to share what we’re learning, as we learn it. In the meantime, here are some helpful resources from organizations and individuals doing excellent work in this field:

- Video: Relationships and learning are inseparably connected.

- The beginning—FELA by Springboard Collaborative

- Ten Ways Schools Can Build Students’ Social Capital

- Mental Health Primer: Transcend’s primer of SEL resources

- Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action

- 2017-Pekel-GettingRelationshipsRight.pdf: Insights and ideas from 55 School Leaders

- 2021 Beginning of Year Relationship Building Toolkit: Flamboyan Foundation

- Videos: The Power of Crew and Identity and Belonging in Crew

- Equity Rubric for Teachers: A method for observing teachers

- Building Equitable Learning Environments: Strategies for building positive classrooms

- Academic-Partnering-Toolkit-for-Teachers-Flamboyan-Foundation: Strategies for teachers

- Supporting Social, Emotional, & Academic Development: Research Implications for Educators