Vision Setting: A Can’t-Miss Step for Curriculum Implementation

In one school system, a new curriculum leads to no change in student learning, causing widespread teacher frustration and complaints from parents. Yet, in another system, the very same curriculum is considered a great success—student proficiency rises, teachers are invested, and parents are happy.

How can the same materials have such different outcomes?

Five years ago, after seeing vastly different experiences with curriculum implementation in our partner schools, we set out to identify the leadership actions that set schools up for success with new instructional materials.

We interviewed educators from more than 70 schools across the country, and our findings were clear: To make a difference in student learning, curriculum selection and implementation need to be guided by a shared, content-specific vision of instruction.

We found that successful teams articulated a vision of how they wanted to transform teaching and learning and then chose a curriculum to support and advance that vision. In other words, they saw high-quality curriculum as a tool to improve teaching and enhance student learning rather than as the end goal in and of itself. Though that may seem like a minor distinction, it can fundamentally change the way schools approach implementation.

Without a clear instructional vision, new materials lead to challenges.

Many of the challenges that we’ve seen educators encounter when selecting and launching a new curriculum can be traced back to an unclear vision and understanding of how the materials will help accomplish it. Examples of vision-related challenges include:

- Selection teams are prioritizing different things during materials review, finding it difficult to reach a strong consensus.

- The curriculum implementation effort is treated as another exercise in compliance—lacking necessary buy-in from key stakeholders.

- There is a lack of coherence across instructional support structures, creating mixed signals for teachers around expectations for using the materials (e.g., professional learning protocols are not connected to the new curriculum).

- Instruction varies widely from classroom to classroom. Teachers’ well-intentioned adaptations dilute the materials, and students don’t end up mastering the grade-level standards.

If any of these challenges resonate, know that it’s never too late to step back and align your team on a common vision of instruction.

Here’s how you can establish a vision of excellent instruction:

Form your team

Before you can establish a new vision of instruction across your school or system, you’ll need a team to write it.

We recommend forming a team composed of, but not limited to, school and system leaders, coaches, teachers, interventionists, and coordinators of special populations (e.g., multilingual learners).

If you’re just beginning your curriculum adoption journey, your vision-writing team should be the same as your materials selection team.

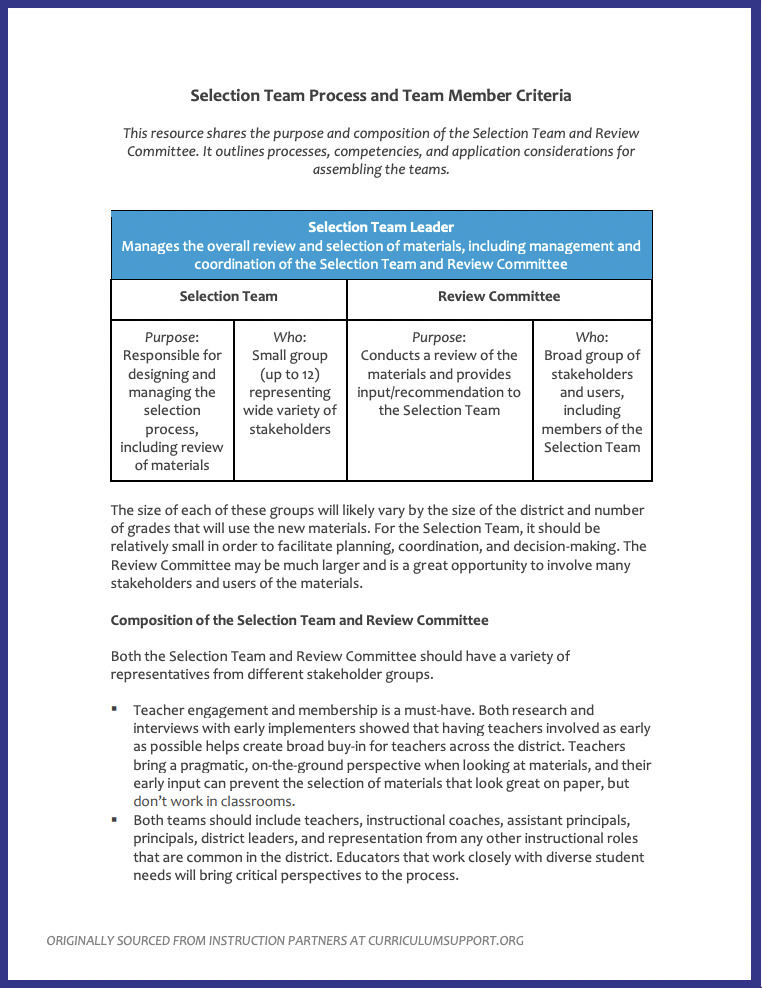

Resource spotlight: Selection Team Process and Team Member Criteria

This resource outlines processes, competencies, and application considerations for assembling selection teams.

Dig into the content and identify core beliefs

Once a team is in place, leaders can develop and facilitate sessions focused on two key questions:

1. What does high-quality instruction look like in this subject area?

This question is not about breaking down the standards but understanding what the standards look like in action, as students experience them. A vision of instruction needs to attend to what is being taught—in other words, the vision statement must be grounded in what the research tells us about how students learn that specific content discipline. Whoever facilitates these sessions needs to know the state standards and content discipline deeply and also be effective at designing and facilitating adult learning.

These sessions should feel a bit like school, doing problems and tasks together as a group. Depending on the subject area, standards training can include:

- Understanding the interlocking aspects of the instructional core, as defined by Richard Elmore: rigorous content, effective teaching, and student engagement

- Reading and discussing research on the best practices for instruction (e.g., understanding the aspects of rigor of the standards in math; understanding the role of foundational skills in ELA)

- Digging into the vertical progression of the grade-level standards

- Experiencing a lesson from high-quality instructional materials that includes the best practices in that content area

- Completing a grade-level assessment, working through text and tasks for the examined standards

We also encourage teams to observe classrooms or watch videos of a lesson together to look for evidence of high-quality instruction. These experiences often reveal differences of opinion that help refine the vision.

Note: This is not a one-and-done training. Leaders and teachers will continually deepen their content knowledge to carry out the vision. Part three of this article provides a helpful guide to planning for content-based professional learning.

2. What are the core beliefs that will be the foundation of our work?

Taking the time to identify your team’s core beliefs about student learning can create a touchstone to return to throughout the selection and implementation process.

For example, a vision for instruction should be grounded in the core belief that all students are capable of grade-level learning. However, we know that simply declaring this belief can sound like fanciful thinking to educators who are already working tirelessly to support students’ unfinished learning from prior grades.

Leaders can respond to questions about students’ capabilities by facilitating discussions that highlight the impact of educator beliefs on student outcomes—especially how low expectations disproportionately affect historically underserved student populations. TNTP has published national studies that can help ground these conversations in research:

- The Opportunity Myth: an extensive study of nearly 4,000 students which found that most students—and especially students of color, those from low-income families, those with disabilities, and multilingual learners—spent the vast majority of their school days missing out on grade-appropriate assignments, deep engagement, and teachers with high expectations.

- Unlocking Acceleration: an analysis of literacy resources in more than 75,000 schools which found that, though students are spending even more time on below grade-level work than they were before the pandemic, students are just as successful on grade-level work as they are on below grade-level work.

Reading and discussing these studies can allow both leaders and teachers to examine how their personal experiences and assumptions may shape their beliefs about what students are capable of achieving. We know that these conversations can be difficult—here are some facilitation tips to support discussions around student expectations:

- Resist the urge to rattle off facts and talking points. Instead, spend time unpacking the research or articles to bring the group to shared ideas.

- Assume best intent.

- Use inclusive language like “we” and “our school community” when responding.

- Make sure everyone in the group has a voice (e.g., “That’s really interesting, X. Y, what do you think about this point?”).

We also encourage teams to examine their schools’ disaggregated student data to understand there may be inequitable learning experiences among their own student populations.

These honest and meaningful conversations allow teams to identify the core beliefs and aspirations that they want to inform instruction for their students.

Resource spotlight: Core Beliefs

This resource provides sample core beliefs for guiding selection and implementation.

Finalize and communicate the vision

Once your team has reached a common understanding of high-quality instruction and aspirations for student learning, it’s time to write your content-specific vision statement.

This resource includes sample statements that you can adapt or use as a starting place for drafting your vision. This also includes sample walkthrough tools, which many school systems use to measure their visions in action.

A vision statement can only guide your community if it’s known and understood by all stakeholders. After finalizing your vision, it’s important to communicate it in multiple ways with your community (e.g., via emails to leaders, teachers, and parents; in a weekly newsletter; during PLC meetings). These communications should include both how and why the vision was created.

When the vision statement is understood by all stakeholders and used as the basis for all decision making, your team can avoid or alleviate the challenges named at the top of this blog. A clear, content-specific vision will provide your school community with common language and help cultivate a cohesive learning community with aligned instructional materials, assessments, professional learning, and teacher feedback.

Want to learn more?

Visit the Curriculum Support Guide for more free guidance and resources to support HQIM selection and implementation.

me

there