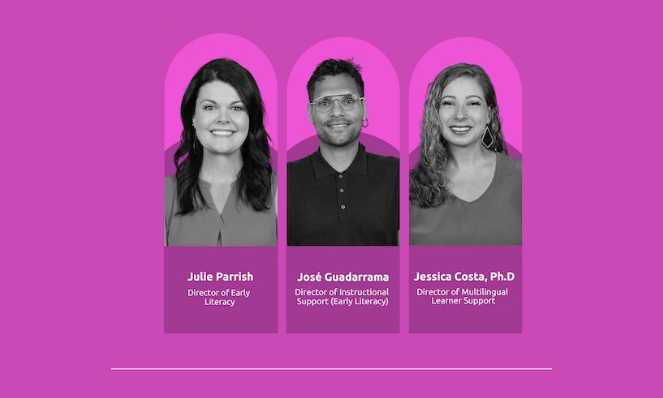

Q&A: Early Literacy Leadership

During a recent webinar, the early literacy team at Instruction Partners answered questions from our audience on a variety of topics related to the Early Literacy Playbook. The most practical and broadly applicable questions and answers from the session are compiled below.

—

This transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity—you can access full webinar recording here.

How were the action sets in the playbook developed?

The playbook was the result of months of reflection on the early literacy work that we’re leading in schools participating in our early literacy pilot. We also drew from lessons we’ve learned from Instruction Partners’ broader services supporting change management within schools and systems across the country—how long things take and what the key steps are. We were very intentional about ensuring that what went into the action sets was based on things that we have found to be effective in our partners’ schools.

How long should it take to work through all four phases of the Early Literacy Playbook?

We expect that this work can be completed over the course of three years. Although the playbook is designed to move through all four phases, the diagnostic resources embedded in the playbook allow you to identify strengths and areas for improvement in each phase so that you can move more quickly to the next. It really depends on your relative strengths and opportunities.

Who should make up the team leading the work of the playbook?

We see the work of the playbook as a reallocation of school system resources, which often necessitates leadership at both the district and school levels. At Instruction Partners, we often work with school-level instructional leaders—including principals, instructional coaches, and teacher leaders. There is a need for continuous support for those school leaders so that they can then support teachers. In many cases, that continuous support for school leaders requires district-level decision making.

Who should be on the district-level team?

It completely depends on the district’s context. A good starting place would be looking through the playbook and asking yourself: What are the decisions we need to make to complete these actions? Include those decision makers in your early literacy leadership team.

What kind of professional development would be beneficial for administrators in this process?

The playbook is predicated on having high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) in place, with the science of reading as the theoretical framework for those materials. We consider HQIM to be the way to bring the science of reading to life. A beginning point for administrators is understanding the structure and content of their HQIM, and how that structure and content relate to the science of reading. We know leaders can’t know every detail of the curriculum, but they can have a working understanding of the expectations of what excellent instruction should look like for each grade level.

To help narrow the focus for leadership development, we ask the leaders we support: At the end of this journey, what do you want your full early literacy team, including our teachers, to walk away with? What knowledge and skills do you need as a leader to be able to guide your team through that work?

If a school isn’t aligned to the science of reading, will the playbook still make sense?

The playbook is grounded in the evidence of how students learn to read. Though the action sets in the playbook would make sense, without high-quality materials aligned to the research of how students learned to read, you likely would not see growth in student outcomes. The playbook may offer a pathway, but if the resources aren’t aligned to HQIM, that pathway wouldn’t necessarily lead to improved student literacy.