Mary Batiwalla, ClassLink

Mary Batiwalla has served in education as a practitioner, researcher, and executive leader. She currently serves as the Director of Evaluation Analytics at ClassLink. In her previous role as Assistant Commissioner at the Tennessee Department of Education, she led assessment development and logistics, accountability, reporting, and data governance. Mary spoke to Emily Freitag about a landscape analysis of academic intervention practices, which she conducted with Instruction Partners.

EF: Mary, thank you so much for joining us today. Please describe for us the project that you did last year to better understand RTI and MTSS models.

MB: This project unfolded over a five-month period and the objective was to try to better understand RTI and MTSS trends occurring in schools across the country. We really wanted to learn how teachers and administrators were perceiving these systems of tiered intervention, what they thought was working for them and where they thought they could use additional support.

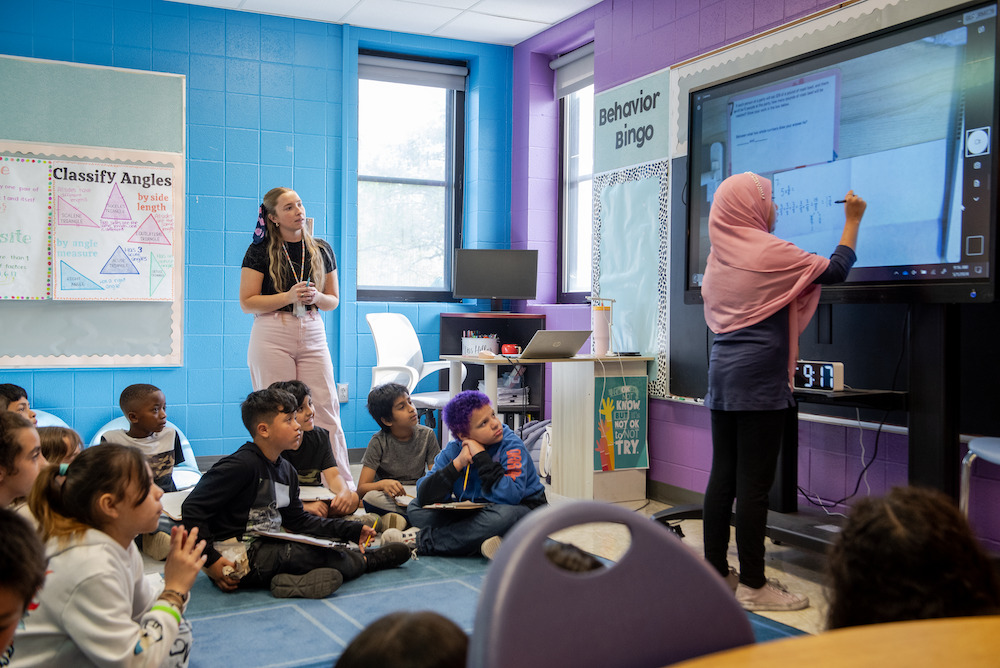

To achieve the objective, we looked across the policy landscape to review the guidance states were giving to districts and schools. We also engaged a number of experts in this area to better understand their perspectives, and surveyed school and district leaders about their practices, the types of products that they were using, their perception of how MTSS and RTI were working in their schools, and the data points they were looking at to best gauge how MTSS was affecting their students. Finally, the really data-rich part of the project involved me visiting nine schools across five different states to talk to educators engaged in the work and observe their interactions with students during RTI and MTSS time.

EF: Tell me more about what you found to be common and true across schools, and what you found to be different.

MB: Folks are doing it—they are engaged in these RTI and MTSS practices. In fact, across sites, for most of the schools that we visited, they had been doing this for a while and were devoting a good amount of resources and time to delivering their version of tiered instruction.

Another thing that really stood out in terms of similarities was that across sites, basically everyone in the school building was involved in the MTSS or the RTI process—whether that be delivering it or attending data meetings. All the schools we visited conducted meetings to really dive into the data that they were collecting around students in RTI. Universally, the schools we visited made RTI and MTSS an intense endeavor and undertaking.

The last thing that really stood out in terms of similarity was that the vast majority of educators I spoke with believed in intervention. They believed in its potential and they believed that they had stories of students who had been positively affected by RTI.

In terms of differences, the way folks decided to deliver RTI varied. Some schools decided it made sense for their schedules to dedicate a block of time—in all places, this was at least a 30-minute block, sometimes it was 45 minutes—where they really focused on delivering Tier 2 and Tier 3 RTI to students who needed it. In other places, they made the decision to deliver the MTSS within the general classroom. Some places used a hybrid of both. Also, individuals expressed different motivations and reasoning for why they were engaged in it.

EF: Can you give some examples?

MB: A number of folks mentioned that they did this to improve their students’ lives; other folks talked about the importance of reading intervention to make reading fun; some folks talked more explicitly about the importance of intervention in terms of improving outcomes for students—outcomes like standards-based assessments. That was one unique viewpoint we saw, where other folks tended to focus more on skills-based assessment and more broadly that kids need to read in order to have a good life. So the types of motivations we saw really did differ across sites.

A few schools really grasped onto the potential of RTI’s ability to achieve equity for students, specifically those students who were historically underserved. Students who were more likely to be receiving intervention in schools came from historically underserved backgrounds, whether that be economically disadvantaged, minorities, or English learners—that really stood out. So in some sites equity was a driving force for the work that they were doing in MTSS.

EF: How did compliance factor for people?

MB: As part of the policy landscape analysis, it came out that some states were heavily focused on using RTI to refer students for specific learning disabilities. What we saw when we visited schools in those states was that intervention became focused on compliance, on meeting all of all the requirements in order to move a student into the “students with disability” classification, particularly for a specific learning disability. We saw it in both Tier 2 and Tier 3, but it really stood out in terms of the practices in Tier 3 instruction—they were much more structured. Teachers in those schools expressed frustration with the inability to truly differentiate in the way they thought was best for students because they felt so compelled to comply with state requirements.

EF: What, if any, insight did you get into what might be working better—and, equally important, what wasn’t working?

MB: In all the sites I visited, nearly all individuals in the school were involved in intervention on some levels, but in some sites, what I saw was not just the involvement of all intervention individuals, but actual deliberate collaboration in thinking through the best ways to deliver intervention for students. That seemed to be key in schools that witness improvement in terms of outcomes. Along with that collaboration, schools that put intentional thought behind how intervention intersected with core instruction seemed to be the ones that saw improvement in student outcomes.

Also, to assess effectiveness of intervention, those intentional, collaborative schools focused on standards-based outcomes. In most sites where there wasn’t a connection, where interventions happened separately from what was going on in the core classroom, educators were really focused on skill outcomes. In those sites, although everyone was touching intervention in some way, they were lacking real collaboration in connecting what was happening in intervention to what was happening in the core instructional setting, and how those things work together to ultimately lift students’ achievement.

EF: Can you paint a more specific picture? So, let’s say in two schools, they’re both reading “The Lightning Thief” in their core instruction. What are you seeing in the intervention where you saw the deeper connection and what is different about what you’re seeing in the disconnected intervention block?

MB: In a school where they’re engaging with that text in the general instructional classroom, a disconnected school setting really looked like students engaging in intervention and not discussing or connecting back to the core instructional classroom materials. For example, they may have had time dedicated to core instruction where they read the text and engaged with core standards, and then at another point in the day, whether in the general classroom work or pull-out, they focused solely on phonics with no connection and very discrete skill sets, and those were the skill sets the school purchased as a secondary intervention curriculum to support students in mastering whatever their skill deficit is.There was a complete lack of connection in terms of what’s happening in the core classroom and what’s happening during intervention time.

On the contrary, in schools where there was intentional connection between intervention and skills-based instruction, they were actually engaging with high-quality materials, like the text you mentioned, to remediate those skills. There were small breakout groups during which they interacted with the material, and for the students who needed additional phonics instruction, the leader of a small group, whether that’s a paraprofessional educator or someone else, provided the remediation within the confines of the standard instruction.

EF: What overarching opportunities do you see for RTI and MTSS based on seeing in different states? What did it leave you thinking about in terms of how it can serve students?

MB: I definitely left thinking there’s great promise with MTSS and RTI and there are opportunities to use the resource and time investments schools are making and improve upon how they are being delivered. I saw both product and policy opportunities. As I mentioned earlier, there were real concerns in state policies that heavily emphasized compliance and it seemed like there were opportunities to shift focus on the potential of RTI and MTSS, not just as a pathway for learning disability identification but really as a pathway to close the achievement gaps that exist for underserved populations.

The work educators are doing around RTI is hard work, and the undertaking is no small task. But, it seemed like there was an opportunity in terms of curriculum products to create something that made intentional connections between skills-based instruction, what’s happening in RTI, and the general classroom. In the school sites that were attempting to make those intentional connections, they did so without any particular curriculum supporting them. They themselves were finding ways to bring skills-based instruction into their core curriculum. In one state there was a guidebook curriculum and they started trying to build in some of those differentiations for tiered instruction. But although generally the product market for RTI and MTSS is saturated, there doesn’t seem to be a product that really speaks to the intentional connections between skills-based instruction and core instruction.

EF: What did educators want more of? What did they say they needed in order for this to go better.

MB: Some seemed to need more professional development to clarify the expectations and the motivations, whereas other people felt they could use additional professional development around best using the assessment and the data to inform their intervention practice. Then, of course, those connections between the core instruction classroom and intervention in general—some administrators really aimed to have the core instruction classroom protected from intervention, so that left big opportunities for collaboration and professional development for educators to understand how those two pieces of the puzzle can really connect for students’ benefit.

EF: So much about RTI feels like it comes down to the skills screener—it’s how you identify students, how you measure progress, how you declare victory, how you orient your instruction. Tell us more about what you found to be the role the screener played, where that role came from, and any opportunities you saw on other approaches.

MB: The screener is a huge piece of the intervention work. All school sites had a screener; it was administered at the beginning of the year and it played a role in placement in terms of whether students were receiving Tier 2 or Tier 3 instruction. A lot of places also used the screener as the identification mechanism for the skill deficit a student needed. That determined where the student went to receive intervention and who delivered it, because a lot of sites grouped based on skill deficit. In schools we visited, the screener was skills-based; it brought in standards-based instruction. To be clear, there were schools that referred to the standards-based assessment data from the prior year, but that took extra effort. Other sites simply looked at the screener data to make these intervention decisions, and they weren’t looking at data coming out of standards-based instruction. Similar to the opportunities for curricular products, there’s an opportunity that needs to go hand-in-hand with those products to really rethink the assessments that screen students for these additional tiered supports.

EF: So you’re talking about a curriculum with an assessment that is both about the standards and has the opportunity to do skills screening in terms of the policy context.

MB: Correct, it would satisfy those requirements and it would touch upon the standards. Current interim assessments don’t break down in the detail needed for students to be placed in tiered intervention. So we need something that provides greater detail on the skill deficits students are struggling with, and one of the key benefits of an assessment like that is it would encourage and set the stage for educators to see intervention as part of the core instruction, rather than “this thing that happens separately over there.”

EF: From what you saw, did RTI seem to be helping kids?

MB: Based on my own observations, I would say in some schools, yes, and in some schools, no. In the school sites where equity was more or less the universal driving factor for educators, and there were attempts being made to connect back to the core instructional materials, there seemed to be moments that I observed where students were being helped by the RTI practices. We don’t know the counterfactual, but when we look at some of the outcome data coming from sites where those practices were being used, those were the only sites where we saw increases in terms of student proficiency and a decrease in terms of the percentage of students scoring “Basic.” Can that be attributed directly back to RTI? It’s hard to say. But I can say that what I witnessed seemed to be powerful, and definitely appeared to be more beneficial than what I witnessed in schools where intervention was a separate activity that happened in 30-minute periods separate from the core instructional environment.

EF: Connecting this to the current moment, what lessons would you share with leaders based on what you saw across these visits?

MB: When I think about the times we’re in now and the potential learning losses occurring, I definitely think the potential of RTI and tiered instruction is more important than ever. One thing that surprised me was that a lot of folks were not using digital products to deliver intervention—given the current circumstances, that’s an important thing to note. It’s unclear how much intervention is actually taking place in a remote learning environment. Although current tools have a lot of room for improvements, they’re going to be critical in helping diagnose the extent of support students are going to need when they come back, hopefully connected to core instruction. I think there’s a lot to be learned about differentiation practices within MTSS systems, and how to use them to help support students who are likely to be in very different places due to this extended time out of school buildings.