Let’s stop asking leaders to be superheroes

This post is adapted from an email originally shared on May 6, 2022. If you would like to receive future emails, you can sign up here.

—

I’ve been struck recently by how often educators are called superheroes.

My boys are all about superheroes right now. My oldest has planned his next four years of Halloween costumes based on the characters in The Incredibles. There is nothing cooler or more awesome than a beloved character with spectacular powers trying to save the world.

In some ways, I like the comparison. Superheroes have super impact, like great educators. They are revered and celebrated, like great educators should be. Especially across the last couple of years, educators have carried enormous responsibility in complex circumstances without a safety net, like superheroes. As I think back on the amazing teachers that impacted my life this week, the feeling of gratitude I have for them rivals the gratitude I would have for Superman’s protection from Lex Luthor.

But, of course, what does it say about the expectations of the job that educators have to possess superhuman qualities to do it well?

I sense education leaders often feel more like imposters than superheroes — and I think this is particularly true when it comes to instructional leadership responsibilities. In vulnerable moments, leaders tell me that they know the instructional buzz words they should use but don’t really know what they mean and that they are afraid to ask because it might reveal that they don’t know something they should. As a system leader, I remember getting a question from an instructional coach about my thoughts on a particular approach to writing instruction that I knew nothing about and feeling intense fear, responsibility, and nervousness as I fumbled an answer. The experience of imposter syndrome is so common among education leaders that it is almost a right of passage in the job.

It does not have to be.

My team and I have been thinking a great deal about how to make the paradigm of instructional leadership clearer these past two years. With support from philanthropic partners, we hired a team to read everything written on the subject, synthesize and find commonalities across all of the frameworks, and co-construct and evaluate different approaches to leadership support with 16 school partners. Our goals were 1) to make the paradigm of instructional leadership clear and practical and 2) to create a mechanism to diagnose and monitor progress to support action.

We started by mapping the leadership competencies that school and system leaders need in order to support instruction, and we tried to support leaders in developing these competencies. As the work progressed, we found we needed a different entry point. We could not help school leaders develop competence in their role until we helped them get incredibly precise on what they needed to do. And we could not help leaders get clear on what they needed to do until we helped them understand the levers they had to provide teachers with effective instructional support.

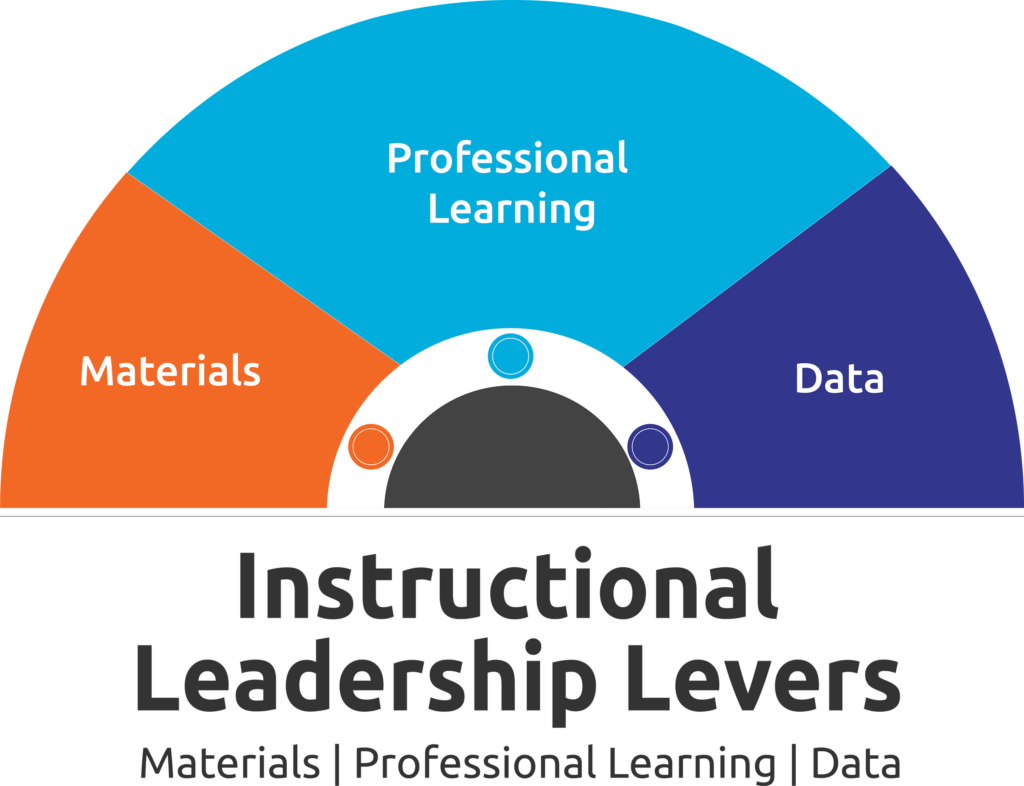

There are three Instructional Leadership Levers leaders can pull to support teaching and learning:

When the leaders in our pilots got clearer on these levers, they felt less like imposters — not only because they had a better understanding of what their role was, but because they had a better understanding of what their role didn’t have to be. Getting practically clear about what unit internalization needs to accomplish gave leaders more confidence in leading the work than they had when they were operating with vague ideas about PLCs. It also made it possible to see how they could share responsibilities and engage others in a way that made the work the joint effort of a team rather than an act of a single superhero.

We try to share what we are learning transparently in case it can support others. We have already released resources to support the materials lever in the curriculum support guide. Over the next month we will be releasing a number of tools that capture what we have learned about the second lever, professional learning.

Education is human work, and teaching and leading will always be hard jobs. We can and should celebrate educators’ extraordinary service. But this project has convinced me that there is so much we can do to make the job easier by making it clearer. And that we will only see results for students at any scale when we get practical about what instructional leaders need to do and the support they need to do it — and, in doing so, stop asking educators to be superheroes.

Here are some resources I have been learning from lately:

- ERS recently released some exciting tools about “Reimagining the Teaching Job.”

- It was energizing to read what is inspiring and motivating these aspiring new teachers.

- I appreciated this op-ed from Natasha Robinson about how other countries approach teaching difficult parts of their history.