How to Strengthen Teacher Learning: A Q&A with Researchers

Instruction Partners is a proud member of the Research Partnership for Professional Learning (RPPL), an organization that brings together PL providers and researchers working to identify the aspects of teacher PL that improve students’ classroom experiences, well-being, and academic growth—digging into what works and how to make it stick.

The organization recently released a research brief, “Building Better PL” which points to features of PL that more effectively improve instructional practice and student outcomes.

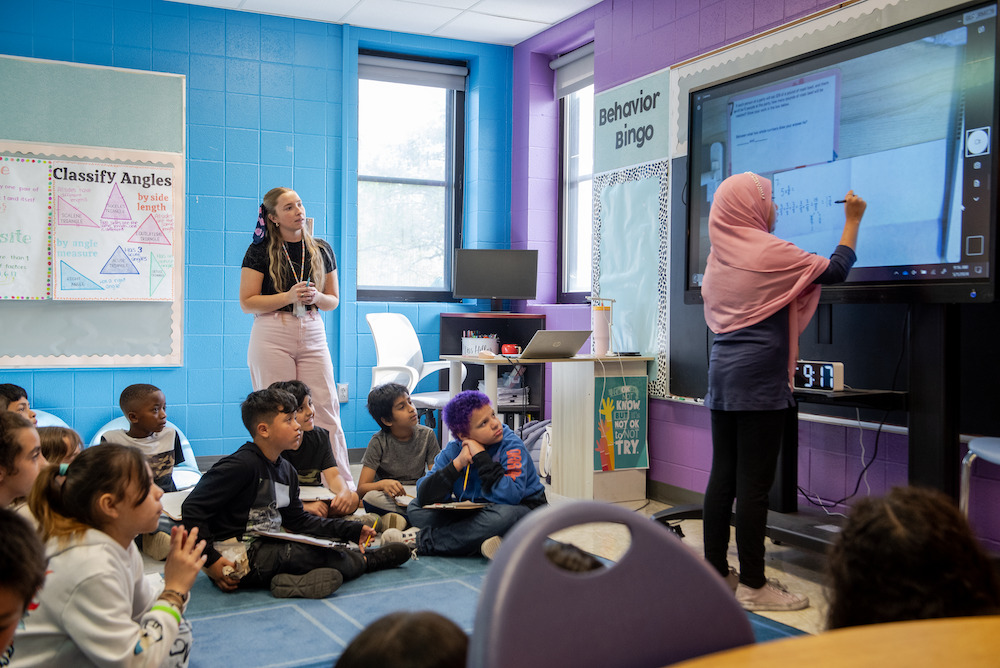

I was excited to see how the evidence shared in the brief aligns to what we are seeing at Instruction Partners in our own work to identify the factors of effective PL. I was especially interested in the recommendation to deliver more PL focused on relationships with students, as my team is currently leading a multi-year project to understand how to center affirming relationships in students’ learning experiences during core instruction.

To dive deeper into this research, I held a Q&A with the authors of the brief, Heather C. Hill and John P. Papay. Here’s their take on how emerging evidence on effective PL features can inform school and system leadership decisions.

—

Were there any findings that surprised you, either because specific strategies were more or less important than you thought?

Yes, two things surprised us.

First, we saw robust support for professional learning (PL) focused on curriculum materials. Across both conceptual reviews of the literature as well as papers with more formal statistical testing, PL programs of this type outperformed programs that did not focus on materials for teachers to use in their classroom. Though scholars have long hypothesized that focusing on curriculum materials in PL could benefit teacher learning, we were surprised at the depth of support in the literature.

Second, we were surprised by emerging evidence that improving instructional practice may benefit teachers in ways that improving their content knowledge does not. State and local governments invested billions of dollars in content-focused PL programs in the early 2000s, teaching teachers the fundamentals of fractions or foundational ideas in number sense. Rigorous studies of several of these programs showed that they did little to move the needle on classroom practice or student outcomes. That was a surprising and humbling finding, because the recommendation for content-focused PL had been based on the best available research at the time. By contrast, programs that improved instructional practice—either with or without curriculum materials to support those practices—did see on-average positive improvements in student outcomes.

We work with many districts that have relatively small instructional leadership teams with limited resources, and we know that educators’ time is a precious resource in any school system. What actions do you recommend for a leader with limited capacity looking to make the most impact with their PL? Does one PL format or strategy have an outsized effect?

Our analysis of the literature suggests two leadership moves have the greatest potential to create an outsized effect: 1) making sure that PL supports teachers’ day-to-day practice and 2) following up PL with some form of social accountability. The first recommendation stems from evidence that successful PL programs start from problems of practice—in teachers’ existing instruction, in district-adopted instructional approaches, in curriculum materials or teacher-identified puzzles to solve—rather than from abstract ideals. The evidence additionally suggests that following up with social accountability—brief peer-to-peer check-ins about how things are going—can help keep implementation of new ideas front and center.

These are general principles, not limited to resource-constrained districts. However, any district, regardless of the resources available, can focus PL on curriculum materials, specific new instructional practices, and other classroom routines. Grade-level teams can budget a few minutes to talk about how implementation of a practice learned in PL is going or designate a peer or principal to stop by classrooms and say, “Hey, how is the XYZ you learned about in PL last week going?”

In our work with school leaders, we’ve found that there are key school conditions—such as a shared vision, clear roles, and dedicated time—that contribute to the success of professional learning programs. In your research, have you seen any enabling conditions for successful coaching and collaborative learning?

Some of the best insights about the conditions for PL success come, ironically, from analyses of failed programs. When scholars investigate why programs fail by talking to teachers and principals, one of the most frequent reasons is a lack of leadership support. This constitutes some of the actions named above—making sure the PL is part of a shared vision, dedicating time—but it also means removing barriers to PL success. Teachers frequently name a few such barriers to implementing what they learned in PL, including conflicting instructional guidance and pressure to focus on other initiatives. Asking for and responding to teachers’ perspectives on the barriers to implementing ideas shared in PL can help improve the chance of meaningful changes to teaching practice.

The focus on targeting subject-specific instructional practices over content knowledge really resonated with me. Can you tell me more about if and how high-quality curricula should be incorporated in a PL focused on instructional practices?

Our understanding of this evidence suggests there are two ways PL can integrate curriculum materials. Some PL programs are designed specifically to help teachers learn to use curriculum materials—for instance, through studying the materials with peers, engaging with the materials as if they were students (e.g., by solving problems), and examining student work from the materials. Other PL programs focus on instructional practices, but the authors of some of these programs write lessons or collections of lessons that support teachers in implementing the new instructional practices. For instance, a science PL program focused on rigorous analysis of classroom video offered teachers educative materials that provided teachers with detailed information about content, anticipated student responses to tasks, and follow-up questions to probe student responses.

Have you come across any findings on the importance of relationships-focused PL that specifically attends to racially affirming interactions? And, how have you seen the impact of relationships-focused PL differ when teachers do not share the same cultural background as their students?

This is a terrific question, but I don’t know of any PL evidence on this specific point. However, there is descriptive evidence that shows identity-affirming classrooms may benefit children. For instance, Anjanette Vaidya and Dr. Dan Battey recently investigated the practice of two Black teachers successful in raising student achievement, showing that they affirm students’ humanity and frame their learners as mathematically capable. This theme of framing students as capable, in fact, appears in numerous studies, with recent authors drilling down on the specifics of this practice. Jonee Wilson’s work, for instance, shows that teachers who promote African-American students’ success explicitly call out the value of students’ mathematical contributions and also implicitly signal students’ capability by gently pushing back on their requests for assistance. By contrast, generic and non-specific praise (“we’re all brilliant math learners here!” ) seemed ineffective.