Unfinished Learning in Reading Comprehension

Are you looking to build your team’s capacity to address unfinished learning? We’re offering customized, content- and role-specific support for instructional leaders. Learn more here.

This week we conclude our tour of content examples of how to support unfinished learning by looking at literacy comprehension.

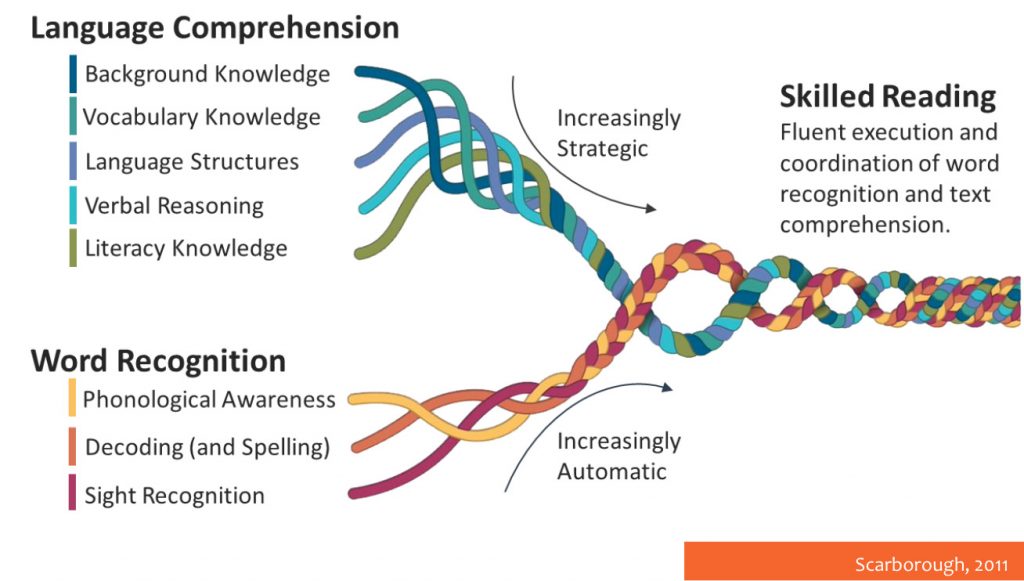

We separated our literacy examples into two parts, because the way students learn foundational skills is quite different from the way students advance comprehension. This is not a grade-band division—students in K–2 need to learn foundational skills and comprehension (chiefly through oral reading) and students in grades 3+ may continue to need support with foundational skills. But leaders benefit from understanding the differences between how children learn to read and how children read to learn; they require different instructional moves.

So what do we know about how students build comprehension? Digging into three of the threads of particular significance for unfinished learning:

- We know that reading does not flow from skill alone; background knowledge matters to our ability to understand what we are reading. The famous baseball study points to the impact.

- We know that vocabulary is critical to language comprehension. According to research, knowledge of individual word meanings account for as much as 50–60% of the variance in reading comprehension. Louisa Moats says that, after learning to decode, vocabulary knowledge is the most important factor influencing comprehension.

- We know there is a series of mental moves readers need to be ready to make when they encounter a sentence they do not understand. Skilled readers make those moves by knowing how to navigate syntax, essentially the grammar of language. Instruction in text structure supports student comprehension and has also been shown to be effective for English language learners.

What does this mean we need to do to support unfinished learning in comprehension?

- Building comprehension flows from practice and experience working with a text. Comprehension skills alone will not build strength in comprehension. To get better at independently comprehending complex texts, students need to engage with complex texts with support.

- Unlike foundational skills, where there is a clear and specific learning progression, there is nothing sequential about text progression. Missing the unit on The Lightning Thief in fifth grade does not prevent a student from digging into The Giver in sixth grade.

- Within a given text, teachers will need to identify the demands and features of the text that will need support. In particular, they need to attend to support for knowledge, vocabulary, syntax, and fluency. While fluency has not always been something secondary teachers support, in the coming years it will become necessary for students who are not yet fluent, as it affects a student’s ability to engage with and comprehend increasingly complex text.

- To have time to provide these supports, teachers will need to slow down instruction, likely covering fewer units in greater depth.

For more on these moves in action, as well as a detailed look at how they show up in a unit on Alexander Hamilton in 10th-grade English, check out the video below and these slides.

Bottom line: To support unfinished learning in comprehension, teachers will need to know the text and their students. They will need to make strategic decisions about how to use time. High-quality instructional materials will support these choices but teachers will need time, especially before each unit, to do thoughtful planning to identify key moments, as well as a wide range of data (observation of conversation, written thoughts, understanding of oral reading fluency) to isolate the key supports.

Addressing unfinished learning in reading comprehension has similarities to math and science:

- Move forward into grade-level content, embedding support within the unit.

- Start with a foundation of strong materials, which makes instructional decisions far more doable.

- Provide teachers time and support preparing for each unit, identifying the key supports from the content, and processing a wide range of data to inform understanding of student needs.

It also has a key difference: Identifying the key support needs in literacy comprehension is driven and organized by the demands and features of text rather than the standards.

This concludes the content deep dives. I’m off for three weeks and will return on July 23 to zoom back out on the takeaways across content areas and talk about what they mean for teacher support.