We know how to teach every child to read (part III of III)

This post is part of a series on early literacy. If you’re looking for more resources for supporting reading instruction, go here.

—

Learning to read English is essential to achievement in every academic subject—and to opportunities beyond schooling. However, learning to read is more complicated in a language the reader is simultaneously learning to speak and understand.

Today, nearly one quarter of children in the United States speak a language other than English at home. That is 10 million multilingual learners. One year ago I would have used the term English language learners (ELLs), the label still used in many places and reporting. But in a change that recognizes the incredible strengths and assets students learning English bring to their school communities, as well as the feat of learning they are accomplishing, multilingual learners is the more accurate description and the term I will use from this point forward.

Even before the pandemic, we saw significant discrepancies between the achievement results of multilingual learners and their native English–speaking peers. The interruptions to schooling have further exacerbated the inequities. The pace of improvement for multilingual learners was, and is, slow—unsurprising given that the go-to practices for effective reading instruction and policy were based on research that openly acknowledged it did not speak to second-language learning.

That said, as summarized well in a recent paper by Dr. Kathy Escamilla, Dr. Laurie Olsen, and Dr. Jody Slavick, we know a great deal about what works in teaching multilingual learners to read.

- We know that our brains learn to read in a second language in a different way than we learn to read in our home language; because the learning process is different, the pedagogy is also different. Effective instruction for multilingual learners makes connections to the structure of students’ home language.

- We know that learning languages is not a zero sum game; in fact, when implemented faithfully, dual language learning programs help students learn English better than instruction that tries to focus learners exclusively on one language.

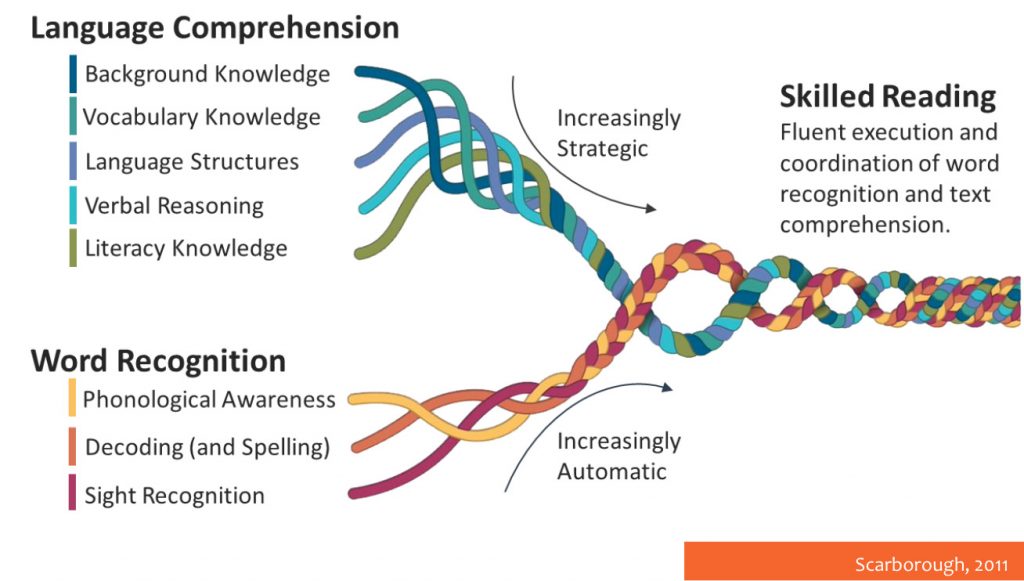

- We know that a narrow focus on phonics and decoding will not serve multilingual learners well—multilingual learners need attention to all of the strands of Scarborough’s ropes, including but not limited to word recognition.

As my kindergartener is learning to sound out words and “break the code,” he will flash in recognition when he connects the sounds coming out of his mouth to a word he already understands. However, I can read a word in German and pronounce it perfectly even if I have no idea what I am saying; there is no flash. As educators, if we do not provide multilingual learners with the right support for meaning, they may learn to “read” in the sense that they can pronounce the words on the page without developing an understanding of what they are reading.

To support multilingual learners, we need to teach them to read in a way that centers their particular learning needs. Unfortunately, the core academic tools available to districts and educators were not designed to support these learning processes:

- Many reading and intervention programs focus on word recognition skills out of context. This may work for monolingual learners but will not support the learning needs of multilingual learners.

- Many teacher preparation and professional learning on reading instruction can undervalue oral language, a critical part of building comprehension for multilingual learners.

- Bridging strategies that help multilingual learners make connections between their home language and English will vary for every language, and educators are rarely supported to know how to make these connections

Until programs are updated or developed to better support these learning processes, the primary lever to support multilingual learners is to provide their teachers support to complement their reading program with these learning needs in mind. This resource includes four classroom strategies to support multilingual learners in early reading instruction, and this set of five essential practices for building an effective early literacy system that centers multilingual learners has practical strategies on how to think about the system of supports.

Across the last few emails I’ve tried to stamp two things: 1) We know that every child is capable of reading; 2) We know a great deal about how to teach every child to read. We do not yet know how to build a system that reliably prepares each and every learner to read. But we are capable of doing this, together.

More students are currently at risk of not learning to read than before the pandemic. Just this week, additional data points emerged showing that the current cohort of K–2 students are furthest behind, and that Black and Latinx students need the most support. The time to put what we know to work is right now.

—

We are looking for 1–2 partners that want to co-design a thoughtful approach to reading instruction that really centers the learning needs of multilingual learners. If you’re interested in digging in more deeply with us in this area, email our Chief Program Officer, Malika Anderson.

—

This post is adapted from an email originally shared on February 18, 2022. Thank you to Dr. Jessica Costa, Director of Multilingual Learner Support for Instruction Partners, for collaborating on this email. If you would like to receive future emails, you can sign up here.