Unfinished Learning in Foundational Reading

Are you looking to build your team’s capacity to address unfinished learning? We’re offering customized, content- and role-specific support for instructional leaders. Learn more here.

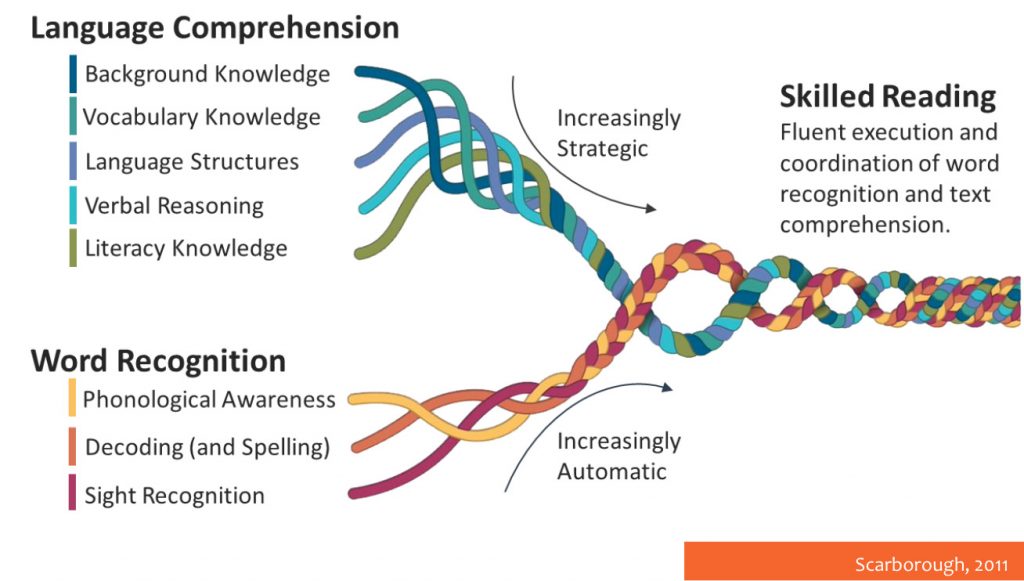

We’ve been touring examples of how to support unfinished learning in different content areas. We looked at addition and subtraction of whole numbers in fourth-grade math and elk population dynamics in middle school science. Now we will look at literacy from two perspectives: word recognition, sometimes called “learning to read” (the red, orange, and yellow threads of the reading rope below), and language comprehension, sometimes called “reading to learn” (the blue, green, and purple threads).

This week, let’s look at word recognition—or, as grouped by the standards, foundational skills.

The ability to recognize and decode words, to turn characters on the page into words with meaning, is a profound human capability. Reading substantially impacts every aspect of our lives, as made clear by the data on the relationship between command of foundational skills and success in all other aspects of learning and life. While we can debate what is and is not important for public schools, we can all agree that equipping every single student with reading skills is an appropriate expectation.

Teaching a child to read is both highly complex and eminently doable work. Of all the content areas, we probably know the most about how to teach foundational reading skills:

- We know that children’s ability to notice and manipulate sound is the first step in foundational skills development. It starts with learning that language comprises different sounds strung together. We then connect symbols to those sounds, unlocking a code we use to interpret and communicate in print.

- We know the English language code is not simple. Letters make different sounds than their name—consider the letter “a” in “cat” vs. “bay.” English has ambiguous sound–spelling correspondences. For example, think about the spellings for the sound “ay” in the following string of words: bake, ballet, maid, straight, gauge, great, veil, grey, and weigh.

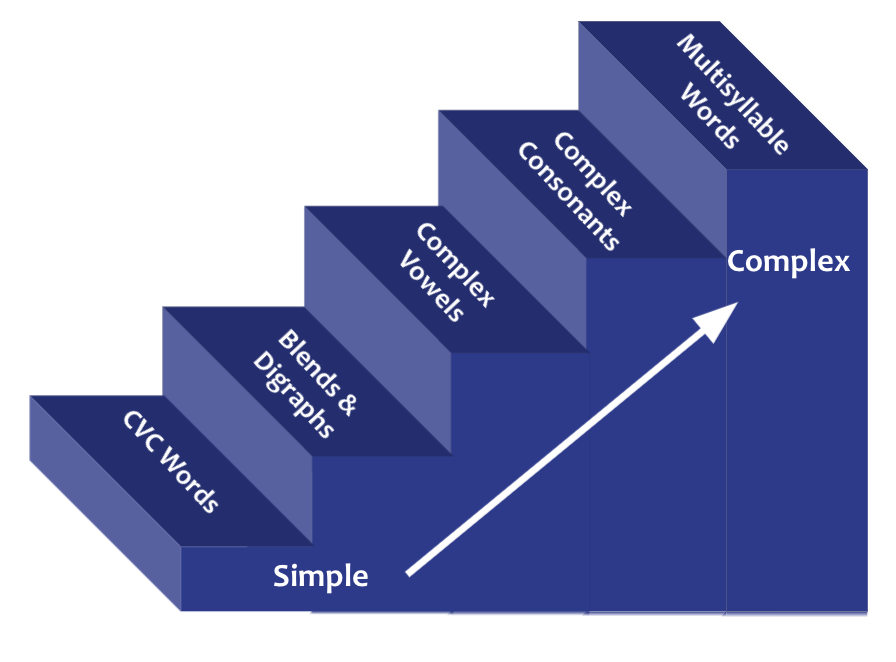

- We know there is a systematic and progressive way to teach children to read. Learning consonant-vowel-consonant words like “cat” before blends and digraphs like “blab” or “fish” is a decidedly more effective approach.

This makes the work of supporting unfinished learning in foundational skills quite different from the approach to unfinished learning in content areas with more entry points and connection opportunities.

In the simplest terms, supporting unfinished learning in foundational skills requires teachers to

- have an exceptionally clear understanding of the specific learning targets each student needs to advance within the progression and

- provide learning experiences that are entirely connected to that specific learning aim.

There are critical whole-group elements to this instruction—every student needs a systematic introduction to the progression of learning with a well-designed curriculum. Supporting unfinished learning will also require targeted individual and small-group instruction during Tier I. Supporting unfinished learning in foundational skills is not something that teachers can think of as “what they get during intervention time” but part of the work of core reading class.

Simple and familiar-sounding steps support this kind of focus for small group instruction:

- Use data to group students

- Set the goals and learning targets

- Plan for instruction focused on learning targets

- Plan for push-in support

- Monitor student progress

The hard part does not seem to be knowing or moving through the steps but rather knowing and moving through the steps with sufficient precision and focus, and getting all the pieces (the curriculum, the assessments, the data meetings, the teacher training) working together in a systematic way so the results are reliable—for every single child, in every classroom.

Interrupted schooling poses all kinds of risks but past examples consistently show particularly dire and lasting consequences for young children, likely because this is such an important chapter for reading foundations. The early literacy data of the past year already gives us cause for extreme concern: this mCLASS:DIBELS study shows an increase in the percentage of students needing intensive midyear reading intervention in the 2020–21 school year compared to the previous year. Roughly 50% of next year’s first-graders (this year’s kindergarteners) showed a need for intensive intervention, compared to about 30% the year prior. This increase gets starker when disaggregated by race: at midyear, the percentage of students performing “well below benchmark” rose 27% for Black students and 25% for Hispanic students, and 13% for white students.

If we cannot effectively support unfinished learning in foundational skills for young students, we will see lasting impact for students and we will all lose out on important contributions. Knowing that first grade is a particularly seminal year in foundational skills, we need to watch closely the first graders of 2020–21—the class of 2032—and hold ourselves accountable to providing the support they need to ensure command of these reading foundations by the time they end elementary school. It is difficult work but entirely within our reach to do so.

There is more to say about how schools can support early literacy success than this email can hold. We’ve been doing some intensive pilots in early literacy and I commit to bringing you what we are learning in more depth, in particular what we have learned about the essential system practices to support effective foundational skills. Stay tuned.

For now, I will summarize by saying that supporting unfinished learning in reading foundational skills is quite different from supporting unfinished learning in math and science. It requires clarity about the systematic progression of learning; precise diagnostics about whether students are behind as well as where they are in progression of learning; and small-group structures that target the particular next step each child needs. However, just like math and science, supporting unfinished learning in reading foundations requires strong core materials to support instructional decisions and intensive planning support for teachers for each unit of study.

For more detail you can watch this video and review these slides.

Next up: reading—language comprehension (reading to learn).